An editor uses a stylesheet to make your book uniquely your own; a proofreader uses it to make sure style is consistent

An editor uses a stylesheet to make your book uniquely your own; a proofreader uses it to make sure style is consistent

What is style?

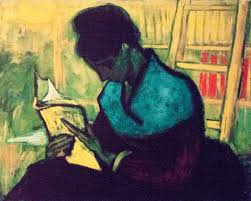

When a writer begins a first draft, it can feel a lot like throwing paint on a canvas. The outpouring of words on a page comes out in fits and starts and eventually the flow begins. Within the flow of a writer’s work, a style emerges.The language rhythm running through a writer’s work can be referred to as their “style.”

Some call this “voice” to delineate an author’s individual quirks and fancies for linguistic flourish. Voice also has to do with substance and theme. What does a writer write about and how? For the reader, style is experienced as seamless to the book experience.

Not only does style indicate an author’s distinctive language usage, it also specifies key terminology for the book such as names of places, characters, objects and ideas.

Style can also refer to the “school” of style a document adheres to: social sciences use APA style, book publishers use Chicago style, news organizations use AP style, etc. Organizations and businesses also may have their own “in-house” style that their communications materials employ.

For a book editor’s purpose, each manuscript has its own style, which is documented in a stylesheet. In publishing, a proofreader uses an editor’s stylesheet to check against the manuscript prior to print.

What’s in a stylesheet?

Once a book draft is complete and revision begins, authorial style can be traced by considering the manuscript as a whole. Style is identified during an editor’s first reading. An editor can help a writer develop a stylesheet by noting all the unusual words that need to be spelled a certain way within the manuscript.

For example, if a character’s name is Jacquie, you’d want to list it in a stylesheet so we know if the character is accidentally written as “Jackie,” we have to edit it. Unique phraseology (made-up words) and uncommon capitalization are also key elements to note.

Stylesheet terms should be listed in alphabetical order to make it easier to look up a term.

Formatting issues can also be addressed in a stylesheet to emphasize structural methodology and design elements within the text. If all interior monologues are italicized, with no quotation marks, the editor might notate this in a stylesheet for a proofreader to review.

If every chapter of a nonfiction manuscript has an introduction, three-point argument, summary and discussion questions, then this might be noted. A proofreader will then know to check that the structure is consistent through the work.

Any formatting notes can come before or after the alphabetical list of terms and phrases and should be provided to a proofreader if available.

Who needs a stylesheet?

Most books have a short list of style items that make them unique. Below I identify some types of manuscripts that benefit from a more in-depth stylesheet.

Series: If an author writes a book in a series, there are sure to be characters and places that overlap from book to book. Stylesheets aid in confirming that character names and locations are spelled correctly in all editions.

Series readers become hooked in part because they know what to expect from each book. If a series follows an established format, such as the opening chapter recaps the series overall, and the second chapter recaps events of the previous book, etc., it should be noted in a stylesheet.

An author can use a stylesheet as a checklist to make sure all the key points of their series style is addressed in a manuscript prepublication. These notes can be as in-depth or as general as is desired or needed.

Sci-Fi/Fantasy: These genre books contain unique worlds and creatures before untold. The power to create and imagine is infinite, and fantasy writers plumb the depths of new universes.

The Select Explorers of Venus the Eighth need to be able to tell their lava-guns from their magma-bombs. So, these proper nouns (Explorers of Venus the Eighth) and new-nouns (lava-guns, magma-bombs) should be identified as stylistically unique entities to remain unvarying in use and spelling throughout the book.

Self-published: DIY writers are often going it solo, so they need stylesheets to keep track of themselves. Double-checking one’s own work can be challenging but is worth the effort.

Developing one’s own stylesheet may also be revealing in terms of self-evaluation. By looking at their work through a stylesheet filter, a writer can see themselves through a reader’s eyes.

Make your style shine

An author might have an idea of their own style. They may even be confident in their writerly voice. But the outside eye of an experienced editor can help a writer identify and enhance traits they didn’t realize the work possessed.

A proofreader can take a stylesheet and make sure a writer’s style shines flawlessly throughout the work. Though admittedly impossible, who doesn’t want to aim for perfection?

A final word on style

No rules say you can’t change your style. Humans evolve, and one’s writing can shift from project to project. So an author’s voice and style may change over time. Yet honoring the readers’ expectations is what keeps me using stylesheets in my work. I want to help writers give readers the book experience they both want.

Val and Mike have a flair for identifying authors’ inimitable voices and polishing their work to develop their style. Contact them for help with your work: heartoflit@gmail.com.